–The following story was written by Taia Goguen-Garner

–The following story was written by Taia Goguen-Garner

Imagine—2 billion years ago, continents that are now thousands of kilometres away were once attached. Sarah Davey, a PhD student in Earth Sciences, is comparing the age and composition of rocks in Finland (Karelia) and Canada (Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba), to test whether pieces of Canada and Finland were once connected and part of a larger supercontinent called Superia.

“I was introduced to this topic through Dr. Richard Ernst in the final year of my undergrad at Ottawa U,” explains Davey. “In terms of being interested in the subject of geology, I’d say that I’ve always found myself captivated by Earth Sciences.”

By looking at igneous rocks that intrude continental crust, Davey is able to gain information about which continents were once attached. Ironically, the rock formations that are studied in order to link together the Earth’s ancient landmasses were formed by the events that initiated and powered their breakup.

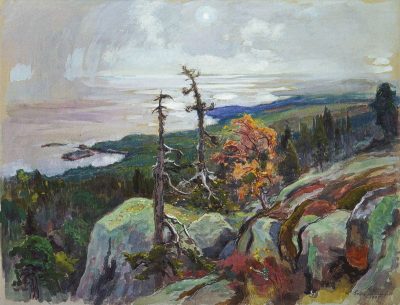

View of Koli (1935) by Eero Järnefelt

One of the most unexpected connections between Finland and Canada is how their kindred landscapes inspired painters in the early 20th century. In Finland, Eero Järnefelt painted scenes of landscapes from the Koli area which, 2 billion years ago, would have been connected to some of the same landscapes that inspired Canada’s Group of Seven.

Davey says that the biggest potential impact of her research would be in exploration for mineral resources such as nickel, copper and platinum group elements (PGEs). This information can help direct industry towards prospective mining areas that may have otherwise been overlooked. Metals such as nickel, copper and PGEs are found in the same rock formations, called large igneous provinces (LIPs), that are studied for the purposes of continental reconstruction. LIPs are also associated with mass extinctions and climate change.

“Rocks belonging to large igneous provinces (LIPs) begin their journey in Earth’s mantle, up to 3,000 km deep,” described Davey. “From the deep mantle, a hot plume rises until it reaches the base of the crust, where it begins to melt and generate magma. The magmas then intrude the crust in cracks as veins and we call these intrusions dykes (which can be traced for 1000’s of kilometers and can range in width from centimeters to a few hundred meters). When or if these dykes reach the surface, the magmas are erupted as lava flows. Overall, LIP magmatism can cover more than 100,000 km2 and produce volumes of magma at least 100,000 km3. To visualize this try to imagine Canada being blanketed by a few tens of meters and, in some cases, up to 8 km of lava.”

Davey is conducting her research by combining the methods of geochronology (determining age) and geochemistry (determining elemental composition) to study the rocks. Specifically, Davey is looking to find geochronological and geochemical matches between rocks from Canada and rocks from Finland. The more matches found, the better the evidence that Finland and Canada were once joined. The exact placement of Finland with respect to Canada can then be determined by spatial relationships observed in the field. By integrating the spatial relationships measured on the ground with geochronology and geochemistry, map patterns emerge that can be used for reconstruction.

For her research she has been able to travel to Finland twice, as well as all over Ontario and Quebec.

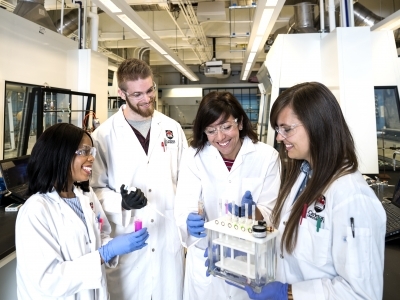

“I do geochronology at the University of Toronto at the Jack Satterly Geochronology Laboratory under the supervision of Dr. Sandra Kamo. We do the geochemistry side of the project at Carleton in the Isotope Geochronology and Geochemistry Research Centre (IGGRC). There, I look at Samarium-Neodymium (Sm-Nd) isotope concentrations in the rocks. These isotopes give us more information about the source of the magmas and specifically about the characteristics of the mantle that was melted.”

Davey’s supervision is a collaborative effort from a number of institutions. Davey is supervised by Dr. Wouter Bleeker from the Geological Survey of Canada and Drs. Richard Ernst and Brian Cousens from Carleton University. Dr. Richard Ernst is also a big reason why Davey chose Carleton for her PhD, as she wanted to join the LIP project he was leading. She emphasises the help that all of her supervisors have provided her throughout her research.

“I have known Richard for almost 9 years and we’ve been working together since September 2010. He’s been my Supervisor for my PhD and MSc projects. Dr. Brian Cousens has mentored me in isotope geochemistry in both lab practices and data interpretation. These datasets are complicated and so it’s essential to have an experienced geochemist to talk out the problems with. Dr. Wouter Bleeker has taught me to be a careful and thorough field geologist and how to integrate data from all aspects of our research to gain a better regional picture.”

Davey is set to continue her research analysing rock age and composition in order to provide more evidence of the ancient connection between Canada and Finland.

Learn more about graduate studies in Earth Sciences.